Decoding Decisions: The 7 Core Elements of Any Decision Situation

We make decisions every moment of every day. From the seemingly trivial, like choosing between coffee or tea, to the monumental, like deciding on a career path or a life partner. Yet, for something so fundamental to our existence, we rarely step back to analyze the *anatomy* of a decision itself. We get swept up in the options, paralyzed by uncertainty, and often rely on gut feelings that can lead us astray.

This is where my experience, both in developing complex systems and in mentoring teams, has taught me a critical lesson: a structured approach is not the enemy of intuition; it’s the framework that allows intuition to thrive. By breaking down any decision situation into its core components, you can move from a state of overwhelming confusion to one of empowered clarity. This isn’t just theory; it’s a practical toolkit for making better choices in your business, your career, and your life.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the seven essential elements of any decision situation. We’ll explore each component in depth, use a real-world business case study to see them in action, and identify the common mental traps that can sabotage your best intentions. By the end, you’ll have a robust framework you can apply to any choice you face.

What Exactly Is a Decision Situation?

Before we dissect it, let’s define our subject. A decision situation is any scenario that presents a conscious choice between two or more possible courses of action, where the outcomes of those actions are uncertain but meaningful to the person or group making the choice.

The key ingredients are:

- A Choice: There must be at least two distinct alternatives. If there’s only one path, there’s no decision to be made.

- Uncertainty: The future is not fully predictable. There is always some level of risk or unknown about what will happen after a choice is made.

- Consequences: The outcome matters. It affects your goals, resources, or future state in a non-trivial way.

“Whenever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision.”

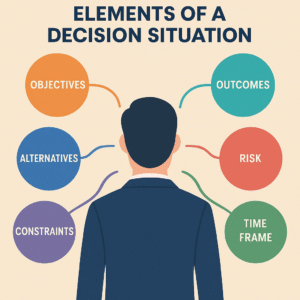

The 7 Essential Elements of a Decision Situation

Think of these seven elements as the control panel for your decision-making process. By consciously examining each one, you gain control over the process instead of letting it control you. Let’s dive in.

1. The Decision-Maker(s)

The process starts with identifying who is making the decision. This seems obvious, but it’s a crucial first step that defines the entire dynamic. The perspective, biases, authority, and values of the decision-maker are the lens through which all other elements are viewed.

- Individual Decisions: When you’re the sole decision-maker (e.g., accepting a job offer), the process is internal. Your personal values, risk tolerance, and goals are paramount. The challenge here is self-awareness and avoiding your own cognitive biases.

- Group Decisions: When a team, committee, or family is involved (e.g., a company launching a new product), the complexity multiplies. You must now manage group dynamics, differing opinions, communication breakdowns, and power structures. The goal is to reach a consensus or an agreed-upon choice that the group can commit to, even if it’s not every individual’s first preference.

Actionable Question: Who owns this decision? Am I the sole authority, or do I need to build consensus with others?

2. The Objectives and Goals

You can’t choose the right path if you don’t know where you’re trying to go. The objective is the “why” behind the decision. What specific outcome are you trying to achieve? A vague goal like “increase sales” is far less effective than a specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goal like “increase online sales by 15% in the next quarter.”

Clearly defined objectives serve as your North Star. They prevent you from getting sidetracked by exciting but irrelevant alternatives. In my years of project management, I’ve seen more projects fail from a lack of clear objectives than from any technical challenge. The team was busy building *something*, but they weren’t sure what problem it was meant to solve.

Actionable Question: What does a successful outcome look like? How will I measure it? What specific problem am I trying to solve with this decision?

3. The Alternatives (or Courses of Action)

These are the different paths you can take—the “what” you can do. A common failure in decision-making is to only consider two options (a “whether or not” choice). For example, “Should we hire this candidate or not?” This binary framing is restrictive. A better approach is to actively brainstorm a wider set of alternatives.

For the hiring example, better alternatives might include:

- Hiring Candidate A.

- Hiring Candidate B from the previous round.

- Reposting the job with a revised description.

- Promoting an internal employee.

- Hiring a freelancer for the short term.

- Automating the tasks instead of hiring anyone.

The quality of your decision is capped by the quality of your best alternative. If you haven’t generated good options, you can’t make a great choice.

Actionable Question: Have I considered at least 3-5 viable, distinct alternatives? What other paths could achieve my objective?

4. The Context and Environment

No decision happens in a vacuum. The context is the set of external factors and constraints you have little to no control over, but which absolutely affect your decision. This can include:

- Market Conditions: Economic trends, competitor actions, consumer demand.

- Technological Constraints: Available technology, platform limitations.

- Legal and Regulatory Rules: Laws, industry standards, compliance requirements.

- Social and Cultural Norms: Public opinion, ethical considerations.

- Time and Resource Constraints: Deadlines, budget, available personnel.

Ignoring the context is like planning a beach picnic without checking the weather forecast. You might have the perfect food and company, but a thunderstorm will ruin your plans. A truly experienced decision-maker is a master of situational awareness.

Actionable Question: What are the external factors, limitations, or trends that I cannot change but must account for?

5. The Information and Data

This is the raw material of a good decision. Information is the knowledge, data, and evidence you gather to understand the situation and predict the potential outcomes of your alternatives. It can be:

- Quantitative: Hard numbers, statistics, financial data, survey results.

- Qualitative: Expert opinions, user feedback, personal experiences, case studies.

A major challenge here is information overload or “analysis paralysis,” where you spend so much time gathering data that you never make a decision. The goal is not to have *all* the information (which is impossible), but to have the *right* information—the key pieces of data that will most significantly impact your evaluation.

Actionable Question: What are the key facts I need to know? What are my assumptions, and how can I test them? Where can I find reliable data?

6. The Potential Outcomes and Consequences

For each alternative you’re considering, you must think through the likely results. This involves forecasting the future—a difficult but essential task. You should consider:

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Outcomes: An option that looks great now might have negative long-term consequences.

- Direct vs. Indirect Consequences (Second-Order Effects): Your choice will have ripple effects. For example, laying off a department (direct consequence) might save money but also crush company morale and lead to key talent resigning (indirect consequences).

- Best-Case, Worst-Case, and Most-Likely Scenarios: This range-of-outcomes thinking helps you assess risk more realistically than just hoping for the best.

Thinking through consequences helps you understand the true cost and benefit of each alternative.

Actionable Question: For each alternative, what is the most likely outcome? What is the best possible outcome? What is the worst possible outcome? What could happen in one year? Five years?

7. The Criteria for Evaluation

Finally, how will you compare the alternatives against each other? The evaluation criteria are the specific standards or yardsticks you will use to judge the potential outcomes. These criteria should flow directly from your objectives.

If your objective is to choose a new company car, your criteria might be:

- Purchase Price (under $30,000)

- Fuel Efficiency (at least 30 MPG)

- Safety Rating (5-star)

- Cargo Space (at least 20 cubic feet)

- Reliability/Maintenance Cost

Often, it’s helpful to assign a weight to each criterion. In the example above, safety might be non-negotiable (high weight), while cargo space might be a “nice to have” (low weight). Using a simple decision matrix to score each alternative against your weighted criteria can transform a subjective debate into a much more objective analysis.

Actionable Question: What are the 3-5 most important factors I will use to compare my options? Are some more important than others?

Key Takeaways: The 7 Elements

To make a robust decision, you must consciously consider:

- The Decision-Maker: Who decides?

- The Objectives: What do we want to achieve?

- The Alternatives: What are our options?

- The Context: What external factors are in play?

- The Information: What do we know?

- The Outcomes: What could happen?

- The Criteria: How will we judge the options?

Case Study: Putting the 7 Elements into Practice

Let’s see how this framework works with a common business scenario. Imagine you’re the owner of “Artisan Roast,” a small but growing coffee shop chain.

The Decision Situation:

Your current point-of-sale (POS) system is slow, crashes frequently, and doesn’t offer the online ordering features customers are demanding. You need to decide on a new POS system.

- Decision-Maker: You, the owner. However, you’ll need to get buy-in from your store managers and train your baristas, so it’s a primary individual decision with group consequences.

- Objectives:

- Reduce customer checkout time by 30%.

- Integrate a seamless online ordering and loyalty program.

- Improve inventory tracking to reduce waste by 10%.

- Stay within a budget of $150/month per store.

- Alternatives:

- Brand A (e.g., Square): Popular, all-in-one system, easy to use.

- Brand B (e.g., Toast): Industry-specific (for restaurants/cafes), powerful features but higher cost.

- Brand C (e.g., Lightspeed): Strong on inventory management, good for retail hybrids.

- Do Nothing: Stick with the current system and try to work around its flaws (this is always an alternative!).

- Context: The local market is competitive, with other cafes offering slick apps and loyalty programs. Customers are increasingly tech-savvy and expect digital convenience. You have a limited budget and can’t afford significant downtime during the switch.

- Information: You gather data by getting live demos of each system, reading online reviews from other coffee shop owners, getting detailed pricing quotes, and asking your managers to test the user interface.

- Potential Outcomes:

- Brand A: Likely to be a quick, easy setup. Might lack some deep coffee-shop-specific features down the line.

- Brand B: Higher initial cost and steeper learning curve, but could provide a superior customer experience and better long-term data.

- Brand C: Might be overkill on inventory but could be perfect if you plan to expand your retail merchandise sales.

- Do Nothing: Saves money now, but you risk losing customers to competitors and continuing to frustrate staff.

- Evaluation Criteria (Weighted):

- Ease of Use for Staff (Weight: 30%): Must be fast and intuitive to keep lines moving.

- Online Ordering/Loyalty Integration (Weight: 30%): A core objective.

- Total Cost of Ownership (Weight: 20%): Hardware + monthly fees.

- Inventory Management Quality (Weight: 15%): Important for cost control.

- Customer Support Reputation (Weight: 5%): Important when things go wrong.

By laying out the decision this way, you move from a vague “we need a new POS” to a structured evaluation. You can now score each brand against your criteria and make a confident, justifiable choice.

Common Pitfalls: Cognitive Biases That Derail Decisions

Having a framework is a huge step forward, but our brains are wired with mental shortcuts (biases) that can still lead us astray. Being aware of them is the first step to overcoming them. Here are a few of the most common culprits I’ve seen in action:

Confirmation Bias

The tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms your pre-existing beliefs. If you already have a favorite POS system in mind, you’ll subconsciously seek out good reviews for it and dismiss negative ones.

How to Fight It: Actively seek out dissenting opinions. Appoint someone on your team to play “devil’s advocate.” Genuinely ask, “What are the reasons this could be a terrible idea?”

Anchoring Bias

Relying too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”). If the first quote you get for a POS system is $5,000, every other price will be judged relative to that anchor, even if it’s an outlier.

How to Fight It: Acknowledge the first piece of information but don’t give it undue weight. Gather multiple data points before forming an opinion.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

Continuing a course of action because you’ve already invested significant resources (time, money, effort) in it, even when it’s clear that it’s no longer the best option. “We’ve already spent six months trying to fix our old POS system; we can’t give up now!”

How to Fight It: Evaluate the decision based only on future costs and benefits. Ask, “If I hadn’t invested anything to date, what would be the right choice to make today?”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the single most important element of a decision?

While all are critical, the Objectives are arguably the foundation. Without a clear understanding of what you’re trying to achieve, you cannot meaningfully evaluate alternatives or determine what information is relevant. Clear goals are the starting point for all rational decision-making.

How is a decision different from problem-solving?

They are closely related but distinct. Problem-solving is the process of analyzing a situation to identify the root cause of a problem. Decision-making is the process of choosing a course of action to address that problem. Often, you must first solve the problem of “what is actually wrong?” before you can make a decision on “what should we do about it?”.

Can I use this framework for small, personal decisions?

Absolutely! You probably won’t write out a formal matrix to decide what to have for dinner. But you can run through the elements mentally in 30 seconds: My objective is a healthy, quick meal. My alternatives are salad, leftovers, or ordering a pizza. The consequence of pizza is feeling sluggish tomorrow. My criteria are health and speed. Suddenly, the salad seems like the best choice. The framework scales to fit the gravity of the decision.

What role does intuition or “gut feeling” play?

Intuition is a powerful tool, but it’s most reliable in areas where you have deep experience. An expert firefighter’s gut feeling about a building’s stability is valuable; it’s pattern recognition built over thousands of hours. A novice’s gut feeling is often just a guess influenced by bias. Use this structured framework first to guide your analysis. Then, check in with your intuition. If your gut screams “no” about the data-driven choice, it’s a sign to pause and investigate further. What underlying factor or risk might your subconscious be picking up on?

Conclusion: From Confusion to Confidence

Decision-making is a skill, not an innate talent. Like any skill, it can be honed and improved with deliberate practice. By moving away from reactive, emotional choices and embracing a structured, analytical approach, you empower yourself to navigate uncertainty with confidence.

The seven elements—the decision-maker, objectives, alternatives, context, information, outcomes, and criteria—are not a rigid set of rules. They are a flexible, powerful framework for thinking. They provide the scaffolding to build a sound, well-reasoned choice, whether you’re leading a Fortune 500 company or simply deciding on your next personal project. The next time you face a tough call, don’t just stare at the crossroads. Take a deep breath, break it down, and make your decision with clarity and purpose.

References

- Cognitive Biases

- Nova Psychology – Understanding Cognitive Biases: How They Influence Our Decisions: https://novapsychology.ca/understanding-cognitive-biases-how-they-influence-our-decisions/

- National Library of Medicine (PMC) – Cognitive bias and how to improve sustainable decision making: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10071311/

- Positive Psychology – What Is Cognitive Bias? 7 Examples & Resources: https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-biases/

- SMART Objectives

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) – Setting Goals and Developing Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound Objectives:1 https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/nc-smart-goals-fact-sheet.pdf

- Walden University – Academic Guides: SMART Goals: https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/success-strategies/motivation/smart-goals

- Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

- 1000minds – Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA/MCDM): https://www.1000minds.com/decision-making/what-is-mcdm-mcda

- MDPI (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute) – Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods and Concepts: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8392/3/1/6

- Wikipedia – Multiple-criteria decision analysis: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple-criteria_decision_analysis

- Expected Utility Theory

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Normative Theories of Rational Choice: Expected Utility: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rationality-normative-utility/

- Investopedia – Expected Utility: Definition, Calculation, and Examples: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/expectedutility.asp

- Scenario Planning

- ResearchGate (from MIT Sloan Management Review) – Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220042263_Scenario_Planning_A_Tool_for_Strategic_Thinking

- University of Pretoria – Scenario-planning in strategic decision-making: requirements, benefits and inhibitors: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstreams/cf831575-b726-4b04-9f77-f6c80f5dd57a/download

- General Decision-Making (Government/Consumer Resources)

- NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) – Resources Related to Investigations and Recalls: https://www.nhtsa.gov/resources-investigations-recalls

- Edmunds – Car Buying Tips & Advice from Our Experts: https://www.edmunds.com/car-buying/

Related Learning Resources

Examples of Passive Leisure

Explore relaxing leisure activities that support well-being and balance.

Why Prioritize Goals?

Learn how short, mid, and long-term goals shape productivity.

Build Effective Task Lists

Understand how to break down goals into actionable steps.

Service Marketing Basics

Discover core principles of marketing intangible services.

Forex Mistakes from Inexperience

See how lack of experience in forex trading leads to costly errors.